by Nancy Jaffer | Apr 7, 2022

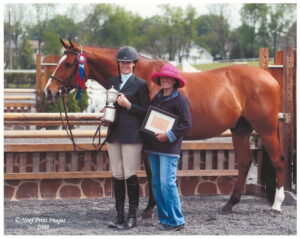

Michael Barisone had “interpersonal problems” and “a longstanding conflict” with student Lauren Kanarek and her boyfriend, Robert Goodwin, in Florida during the winters of 2018 and 2019, according to Dr. Louis Schlesinger, a psychology professor at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice, who was a rebuttal witness for the prosecution today in the dressage trainer’s attempted murder trial.

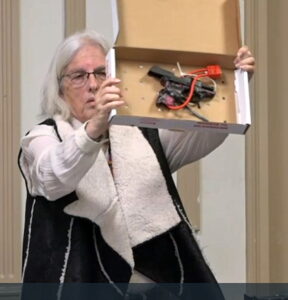

Psychologist Louis Schlesinger makes a point during Barisone’s trial. (Photo © 2022 by Nancy Jaffer)

Since the combo of Kanarek and her partner wasn’t a match made in heaven for Barisone, why did he let them come back to his Hawthorne Hill Farm in Washington Township, N.J., for the fateful summer of 2019, when Kanarek was shot?

“He said he needed money,” explained Schlesinger, noting that it cost Barisone $36,000 a month to run his business. The 2008 U.S. Olympic dressage team alternate told Schlesinger everyone in the horse business has to deal with difficult clients, so he lived with it. Kanarek was paying $5,000 monthly board for two horses, although she had several other mounts, one of which she bought from Barisone for $30,00 or $40,000; the amount stated has varied.

At the same time, Goodwin was doing some construction and tileing in the farmhouse on the property where they lived and elsewhere on the farm, but he wanted to be paid for his work. Barisone had been trying to get the couple to leave his farm, and was moving ahead with eviction procedures.

This was the final afternoon of testimony in the trial that has lasted nine days in Morristown, N.J., with attorneys set to sum up and the jury getting the case next Monday. We finally got some answers to questions that have arisen as Superior Court Judge Stephen Taylor presided, but were left open-ended due to objections that were sustained or otherwise not permitted. You can’t appreciate the intricacies of the rules of evidence until you see how many “sidebars” are called, where the lawyers move to the bench to discuss various issues in low voices with the judge.

Michael Barisone confers with his attorney, Edward Bilinkas. (Photo © 2022 by Nancy Jaffer)

Schlesinger, who has worked for government agencies including the FBI and the Morris County Prosecutor’s office, with which he is presently involved in another case, was called by the prosecution to comment on the testimony of the expert witnesses for the defense.

They are a psychiatrist and another psychologist, who discussed Barisone’s mental state. A psychiatrist is a physician who can prescribe medicine; a psychologist is a PhD who specializes in the study of mind and behavior or in treatment of mental, emotional, and behavioral issues.

The psychiatrist, Dr. Steven Simring, yesterday said Barisone–who had been seeing a therapist on and off for 20 years–suffered from delusional disorder and also was dealing with persistent depressive disorder.

Barisone stated he couldn’t remember the incident in which he is charged with shooting Kanarek twice, resulting in her stay of nearly three weeks in Morristown Medical Center’s intensive care unit.

Simring said being hit on the head with a phone by Goodwin “is probably the most likely reason Barisone lost memory,” noting he suffered several injuries on his head, including a hematoma behind his ear. Dr. Charles Hasson, the defense team’s psychologist, mentioned Barisone had many head injuries over the years, a not-unfamiliar scenario for equestrians.

Defense psychologist Dr. Charles Hasson. (Photo © 2022 by Nancy Jaffer)

Schlesinger, however, was skeptical about Barisone’s memory loss, noting it came after the attack, when Goodwin punched the trainer and then held him down on the ground until the police came.

Defense attorney Edward Bilinkas is pursuing a joint insanity and self-defense strategy, so the psychology experts are key to judging Barisone’s mental state.

Defense attorney Edward Bilinkas. (Photo © 2022 by Nancy Jaffer)

Schlesinger discussed malingering in terms of feigning or faking an illness, motivated by criminal prosecution.

He said it is something that is “strongly suspected” if an individual is referred by an attorney when charges are pending.

The fact that Barisone remembered what happened prior to the shooting and afterward, but not the incident itself is “a red flag. Why isn’t everything blacked out?” Schlesinger wondered.

He maintained, “There’s no memory disorder that is selective just for criminal conduct. So what does he not remember? Lauren comes out (of the farmhouse) and then he has no memory for anything else until he wakes up in the hospital with a big light on him.”

When something like that happens, Schlesinger suggested, “the first thing you say is `Where the hell am I? Why am I here?’ He didn’t say that.”

Schlesinger mentioned dissociative amnesia “that can occur in a trauma, so I considered that.”

But he added, “I don’t think that is correct. I think this is malingered amnesia” noting it is “very common in criminal cases.” He observed, “There is no memory disorder that is selective just for criminal conduct.”

Although Barisone owned several guns, the weapon used in the shooting was a pink and black 9 mm Ruger belonging to Ruth Cox, who co-owned horses at the farm. She would travel up from North Carolina to visit with a gun in her car because she was concerned for her safety while traveling.

Barisone asked her for the gun after she arrived in early August and put it in his office safe because “he felt it wasn’t safe in the car with Lauren there,” Schlesinger reported.

“Does it show anything with respect to whether he know or appreciates the nature and quality of his actions,” asked Morris County Supervising Assistant Prosecutor Christopher Schellhorn.

Morris County Supervising Assistant Prosecutor Christopher Schellhorn and Assistant Prosecutor Alex Bennett.( Photo © 2022 by Nancy Jaffer)

When Cox arrived on Aug. 2, 2019, “The gun was in a case and the ammunition was not loaded,” the psychologist said. But the gun was out of the case and loaded when Barisone drove to the farmhouse where the confrontation with Kanarek and Goodwin took place on Aug. 7, 2019.

Schlesinger commented on “Michael’s belief that Kanarek was going to kill him, Mary Haskins (his former girlfriend) and her children.”

He said, “It’s not delusional, it’s based on what was going on at the time.” He noted that Haskins felt their lives were in danger and thought Kanarek’s father, Jonathan, was going to kill her.

But Schlesinger contended that had nothing to do with the shooting. Instead, he maintained it was sparked when an investigator from the Division of Child Protection and Permanency came to the farm to speak with Mary Haskins, who, like Barisone feared the children would be taken from her.

“Who wouldn’t be upset if he incorrectly thought Lauren called Child Protection? She didn’t, but that’s what he thought,” said Schlesinger.

“My understanding is that SafeSport called DCPP.”

However, earlier in the trial, it was brought out that Kanarek had twice looked up the anonymous reporting number for DCPP.

Drs. Hasson and Schlesinger disagreed on methodology involving a series of psychological tests, which left a question mark on which accurately assessed Barisone’s mental condition.

The issue, according to the judge “is what’s in the defendant’s mind.”

by Nancy Jaffer | Apr 6, 2022

An increasingly panicked and desperate Michael Barisone was trying to get help as his life was spinning out of control, a psychiatrist testified today in the dressage trainer’s trial on attempted murder and weapon charges.

The expert witness, Dr. Steven Simring, concluded Barisone suffered not only from delusional disorder but also was dealing with persistent depressive disorder, noting he had been seeing a therapist for years.

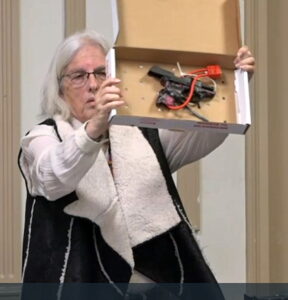

Dr. Steven Simring holds up a report given to him by Michael Barisone, part of his stack of papers that includes police reports and Facebook postings. (Photo © 2022 by Nancy Jaffer)

Barisone, the 2008 U.S. Olympic Dressage Team alternate, is charged with shooting his student, Lauren Kanarek, who was a tenant in his farmhouse with her boyfriend, Robert Goodwin. He was trying to get them to leave his Hawthorne Hill farm in Washington Township, N.J.’s Long Valley section, and obsessed over Kanarek’s social media postings. He believed she was destroying his life and planned to kill him.

That fear changed him from “a remarkable guy” and “a fantastic horseman,” as Olympic eventer Boyd Martin put it, to a deeply troubled shadow of himself,.

Martin took the stand before Judge Stephen Taylor in Superior Court, Morristown, N.J., to testify about how Barisone was viewed in the equestrian community.

“He was one of those people you are drawn to, larger than life,” said Martin. He recalled how Barisone was so dedicated he would leave New Jersey before dawn to get to Martin’s Windurra Farm in Pennsylvania, arriving before the eventer was even out of bed in order to get ready to train him.

As happened yesterday when fellow eventer Phillip Dutton testified, the subject of a barn fire at a stable Martin was renting in 2011 came up. Six horses died in the blaze, caused by a faulty hay steamer.

Defense attorney Chris Deininger asked Martin, if had he been at the barn that night and noticed the machine was faulty, “would you have done something to address it?”

Boyd Martin is sworn in as a witness in the Barisone trial. (Photo © 2022 by Nancy Jaffer)

Martin was not allowed to answer after the prosecution objected. The question related to Robert Goodwin’s agitation about a dryer that wouldn’t turn off in Barisone’s stable in 2019. Outside court, several people mentioned they had wondered why Goodwin just didn’t unplug the dryer if he was upset about it.

Most of the morning was taken up with testimony by Simring. Under questioning by lead defense attorney Edward Bilinkas, the doctor noted, “Mr. Barisone was trying everything within his power to stop the relationship between him, Kanarek and Goodwin. He wanted them off his property. They didn’t want to leave. They claim they had a right to be there.

“Mr. Barisone said he was scared to death of Lauren Kanarek.”

The trainer “became increasingly desperate, because he saw himself in a situation in which he was being physically threated by Lauren Kanarek and Robert Goodwin. He felt trapped. He felt there was no way out. He was afraid he’d be killed and wanted to defend himself.”

He noted that Barisone also was upset about having his conversations recorded after he found things he had said privately being quoted on Facebook. He hired a company to sweep his property to find the bugs.

The psychiatrist sat behind an eight-inch-high stack of papers, which included 19,000 of Kanarek’s Facebook posts that had intimidated Barisone, as well as various police reports and other items relating to the case, including a 91-page report assembled by his patient.

Simring spoke with therapist Ann Picardo, whom Barisone had seen for 20 years when she treated him for depression and anxiety.

Michael Barisone talks with Patrick DeFranciso in court. (Photo © 2022 by Nancy Jaffer)

“I learned from her he came from a family which was emotionally and physically abusive. One of the maternal grandparents suffered from depression,” said Simring, noting he believed that person had required shock treatment.

“Depression runs in families,” said Simring, noting Picardo described Barisone as “very troubled” and “thought he was at considerable risk for suicide,” even before the incident. He told the therapist that he “had lost everything.”

Simring commented that as Barisone’s disturbance grew, “everyone noticed he was no longer the same person.”

While Barisone remembered what had led up to the shooting and what happened afterward, he couldn’t remember the incident itself, Simring said.

“One of the things seemed to be that Robert Goodwin hit him on the head with a cellphone and that is probably the most likely reason he lost memory,” the psychiatrist said, commenting that Barisone suffered a hematoma behind his ear and other injuries.

Dr. Charles Hasson, a psychologist, also testified today, noting Barisone was emotionally unstable and had researched getting assisted suicide in Switzerland in 2015.

Hasson had Barisone do a battery of tests, which showed among other things he scored very high in paranoia and anxiety. He was “very prone to making idiosyncratic deductions,” combining them “in a way that doesn’t make sense.”

He noted that over the years, Barisone had eight to 12 concussions and a skull fracture. People who ride often suffer concussions when they fall off.

Noting how frightened he was of Kanarek and Goodwin, Hasson quoted Barisone as saying, “these are dangerous people” and worried about the fate of the horses at his farm and the children of his then-girlfriend, Mary Haskens Gray, if something happened to him.

The day ended with Morris County Supervising Assistant Prosecutor Chris Schellhorn doing a back-and-forth with Hasson about the validity of his testing process and mentioning that “feigned amnesia is found more frequently in individuals with legal problems.”

by Nancy Jaffer | Apr 3, 2022

Beloved Illinois trainer Nancy Whitehead has died. She was found on a recliner in her condo yesterday. An autopsy is being conducted to determine the cause of death, according to her longtime friend, Nick Novak.

Nancy was the winner of the U.S. Hunter Jumper Association’s 2020 Jane Marshall Dillon award, which honors instructors who gave their students the right start.

Her most famous student in that regard was Kent Farrington, an Olympic medalist who has been a winner at the world’s biggest horse shows.

“Nancy was always very generous with her time and tried to give me as much riding opportunity as possible, riding everything from new horses that had come off the racetrack to riding horses for amateur clients she had at the time,” recalled Kent.

Nancy was a talent-spotter for both riders and horses.

She knew early on it was important to burnish Kent’s ability, telling his mother, Lynda, “You realize your son will probably go to the Olympics one day?” And so he did, having been to the Games in 2016 and 2021.

Nancy was more than a trainer and instructor; she was also a positive thinker, as well as a breeder, and someone who is empathetic and sympathetic to her students. She knew how to give horses an opportunity to do well..

“I will always remember a great lesson from Nancy, in that every horse deserves a chance to see what it could do,” Kent said.

“Even if the horse was very unconventional, too small or extremely difficult to ride, that didn’t mean that it couldn’t be a great horse in the competition arena. That sense of an open mind with horses and trying to make every horse be the best that it can be at whatever level that is, remains a way of thinking that I carry with me today.”

by Nancy Jaffer | Apr 3, 2022

“She was a horsewoman through and through, to her core, and every moment we got to spend with her made us better horsewomen and better people. She was a class act.”

Horses were the focal point of Sandy Lobel’s life. (Photo courtesy of Aaron Lobel)

That’s how Sandra Nagro Lobel was remembered by a former student, Elizabeth Blaisdell, as she reminisced following the trainer’s death on Wednesday.

Sandy, 78, had been fighting cancer but was still very involved in her profession, guiding the careers of amateur riders and the show hunter, Cypress. Elizabeth who started working with Sandy in her youth, said Sandy also helped her 11-year-old daughter, Ella, at the end of last year and into February.

“She instilled a sense of confidence in me. I think that comes from just good, old school horsemanship,” Elizabeth commented.

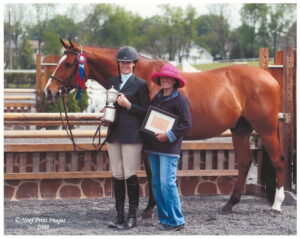

Sandy with Trendy, a favorite hunter. (Photo courtesy of Aaron Lobel)

The daughter of legendary horseman Clarence Nagro, who ran Hilltop Stable in New Vernon, N.J., Sandy had the same feel for a horse as he did.

It was obvious that the apple didn’t fall far from that tree.

She spent much of her life in New Jersey. Sandy operated under the Ravens Wood Farm name in Bedminster before moving to Ocala, Fla. Wherever she went, she made an impression.

“Sandy could be fierce, but she was also fiercely loving and loyal,” recalled Jazz Johnson Merton.

“She taught me how to persevere. `Stop saying I can’t’–she must have said this to me a thousand times. As a coach and a friend, she insisted that I was made up of more than I knew. ”

Sandy with Jazz Johnson Merton. (Hoofprints Photo)

Sandy had a reputation for energy and dynamism.

“Never circle, keep moving forward, never give up. She rode this way, taught this way and fought this way until the very end,” Jazz observed.

“Sandy loved deeply even when she didn’t show it, and she will be loved and missed by us all, always. ”

Sandy’s son, Aaron, noted, “She was a very strong woman. I admired her strength.

“I’ve never seen anyone as compassionate toward animals the way she was; she would stop and rescue a mouse off the side of the road. She taught me how to bring back baby birds that fell out of the nest.”

Sandy with her son, Aaron Lobel. (Photo courtesy of Aaron Lobel)

Bethie Walters Dayton called Sandy “a very kind person. She would always help people out. Somebody in need? She was the first one to give them what they needed.”

Anna Ross, who worked for Sandy for 45 years, said “She was like my second mother. I learned a lot from her. She was amazing. She loved animals and they loved her. She could get a combination of a horse and rider to the top levels.”

Charlotte Thall, who rode with Sandy for 28 years, said “she was a huge part of my life, both in and out of the ring.”

Sandy with Lilly Thall in the leadline at Devon. (Photo courtesy of Aaron Lobel)

“She was an amazing horsewoman and teacher,” commented Elizabeth Devor, who rode with Sandy for 10 years.

In addition to Aaron, Sandy is survived by her brother, John Nagro; a niece, Patty Nagro, and a nephew, Michael Nagro.

A celebration of her life will be held in Ocala at a date to be determined. Plans call for a perpetual trophy to be presented in her memory at a hunter event, perhaps with a donation from that event to go to a charity.

In the meantime, those who wish to make a contribution in her memory may do so for Danny & Ron’s Rescue at this link.

by Nancy Jaffer | Apr 5, 2022

(There is a correction in the 15th paragraph)

Just days before the shooting of Lauren Kanarek, wheels were in motion to have her leave dressage trainer Michael Barisone’s farm, where testimony in his attempted murder trial revealed the atmosphere had become poisonous.

Kanarek, who came to Barisone for training in 2018 and lived in his farmhouse with her boyfriend, Robert Goodwin, had refused to depart his Hawthorne Hill stable in the Long Valley section of Washington Township when he asked her to leave. She had contended it was difficult to locate a stable that could take her five horses.

But Barisone’s lawyer, Steven Tarshis, had negotiated in July and early August with her father, Jonathan Kanarek, and found a comparable stable in the area that would take her, according to testimony today in Superior Court, Morristown, N.J.

“I believed we had an understanding,” said Tarshis, who was looking for a non-judicial way to get her to go elsewhere, though he noted Kanarek didn’t leave.

Michael Barisone’s personal attorney, Steve Tarshis. (Photo © 2022 by Nancy Jaffer)

On Aug. 5, a letter demanding she get off the property was delivered to Kanarek by email. She was served with a complaint, but it had never been filed.

“Michael did not want to start eviction, he wanted to scare her into leaving,” Tarshis said.

“So we suggested serving her with the papers, but not filing them, hoping this alone would give her the impetus to honor the agreement we thought we had.”

He mentioned the atmosphere at the farm was “getting worse and worse almost by the day,” and wondered how reports of personal private conversations he had with Barisone appeared on social media.There had been testimony about secret recordings earlier in the trial.

Seeing the conversations posted publicly “was really disturbing,” he said, noting the only way Kanarek could have heard them was to be in the room while they were talking, but she wasn’t.

Fate conspired against a solution when a caseworker from the state Division of Child Permancy and Protection arrived on Aug. 7, 2019, to talk to Barisone’s girlfriend at the time, Mary Haskens Gray, the mother of two.

Barisone went into his office, where the caseworker and Gray were meeting, and asked them to leave. The office was where he kept a 9mm Ruger pistol in the safe. Then he drove to the farmhouse and Kanarek wound up with two bullet holes in her chest.

During the trial, it was revealed that she had looked up the number for the division’s hotline on her phone, but it has not been made clear yet who notified the agency.

Yesterday, Morris County Supervising Assistant Prosecutor Christopher Schellhorn quoted firefighter/paramedic Daniel Vitale, who treated Barisone after he was involved in a struggle with Goodwin following the shooting. Vitale said Barisone told him, “Someone drove down my driveway and said she was going to take my kids. That’s all I remember.”

Washington Township Police Cpl. Thomas Falleni was questioned by Barisone’s lead attorney, Edward Bilinkas, as to how he collected information at the scene of the shooting.

He said he searched Barisone’s pick-up truck, but not other vehicles at the scene, and asked to have Barisone’s hands swabbed for gunshot residue, but said no residue testing was done on anyone. (This is a correction; the story previously said Barisone’s hands were swabbed.)

The corporal did not seize any video cameras, including one that had a view of the area where the shooting took place.

Several high-profile equestrians testified on the seventh day of the trial about how much Barisone had helped them in their careers, citing his coaching expertise, with some expressing concern about his condition as he agonized over the situation with Kanarek and Goodwin.

Allison Brock, coached by Barisone to a team bronze medal on the 2016 Olympic dressage team, was alerted by another professional equestrian, Jaime Dancer, that Barisone was “upset and distraught.”

Olympic dressage medalist Ali Brock was worried about her mentor, Michael Barisone. (Photo © 2022 by Nancy Jaffer)

Dancer said, “I thought he was going to kill himself.” She noted he had taken to pacing, like a horse that that is stressed.

When Brock heard from Dancer, she called Barisone, whom she had met in 2002 and considers a close friend.

“He was very quiet,” she said, noting that was “unlike Michael,” and discussed their conversation when he told her about the situation at his farm.

By the end of the phone call “he got more upset, sobbing hysterically,” Brock reported.

Eventing Olympic multi-medalist Phillip Dutton started working with Barisone on the dressage phase of his sport about the time of the 2012 London Olympics and a few years thereafter.

“All of my interactions with Michael were extremely honest,” said Dutton, calling him, “someone I could trust.”

There was a startling moment as his testimony ended, however, when Schellhorn brought up a 2011 fire caused by an electrical short in which six horses died at Dutton’s Pennsylvania farm.

“I’m sorry to ask you this question,” he said.

“Is it fair to say a barn fire can be dangerous for the horses?” he queried

“Absolutely,” Dutton replied.

Phillip Dutton testifying at the Barisone trial. (Photo © 2022 by Nancy Jaffer)

I wondered about the relevance of that query, but it could well be linked to earlier testimony that Goodwin had made an issue about the danger of a dryer that wouldn’t turn off in the Hawthorne Hill barn.

Another witness, Jordan Osborne, a working student for Barisone, was asked by another defense attorney Chris Deininger whether she ever felt threatened by Goodwin. The prosecution objected. Judge Stephen Taylor chastised the lawyer and told the jury the comment was stricken from the record.

Schellhorn asked the young woman whether her mother is Lara Osborne, and after getting an affirmative reply, said, “What’s the nature of her relationship with Michael Barisone?”

Osborne said, “They’re in a romantic relationship.” The defense objected, but was overruled.

Deininger then asked, “You swore under oath to tell the truth when you were brought here this morning. Would you violate that oath simply because of a relationship your mother was having?”

“Absolutely not,” she replied firmly.

Jordan Osborne said when Washington Township police came to the farm after being called as the facility became increasingly dysfunctional in the days before the shooting, they weren’t interested in doing anything about the situation. She described them as “very nonchalant. They turned around and walked away.”

Sean Cullen, a licensed professional counselor in psychology, met with Barisone Aug 9, two days after the shooting.

He testified about “a steady build of stressors in his life” that became acute in the days before the incident.

As Barisone discussed during their meeting what had been a volatile situation at his farm, Cullen recounted, the trainer said about his interaction with the police, “I kept telling them this was going to come to a boiling point.”

by Nancy Jaffer | Apr 4, 2022

A truck driver hired by Michael Barisone to keep watch over the dressage trainer’s stable amid discord at the property said his friend was “so messed up he could hardly even talk.”

An ongoing dispute between Barisone and two tenants he was trying to evict from his Hawthorne Hill farm created a toxic atmosphere that culminated in the Aug. 7, 2019 shooting of his dressage student, Lauren Kanarek, who lived in the house at the facility with her boyfriend, Rob Goodwin.

Barisone, who is being tried in Morristown, N.J., for attempted murder and weapon possession in the case, would walk his property in the Long Valley section of Washington Township, N.J., three or four times a night as he sought to insure the horses and people were safe.

“He was beside himself,” according to the driver, Lawrence Davidson, who started his nightly vigil at 8 p.m. during the week before the shooting.

Davidson was among the witnesses today as the prosecution rested and attorney Ed Bilinkas began his defense of the 2008 U.S. Olympic dressage team alternate. He is pursuing a combination insanity and self-defense strategy, showing how Barisone became desperate as tension with his tenants increased.

The last prosecution witness was Essex County attorney Edward David, who had met with Kanarek, Goodwin and Kanarek’s father, Jonathan Goodwin, also an attorney, about the eviction situation.

Attorney Edward David on the witness stand.

To put this in context, in his opening statement, Bilinkas had stated, “What this case is really about is about Lauren Kanarek, her father and her boyfriend devising a plan to destroy this man (Barisone) and drive him crazy.”

David said he was on the phone with Kanarek when she was shot. He was calling to give her good news about progress in reaching a resolution on the eviction issue with Barisone’s lawyer.

He described his conversation as, “one of the wildest phone calls” he ever had in his career. As he spoke to Kanarek, she told him, “Oh my God, I’ve been shot in the chest.” He said he heard what he thought were gunshots “but you don’t want to believe it.” However, he believed it enough to dial 911.

David had some trouble remembering things, excusing that by saying the shooting was four years ago. Actually, it was less than three years ago.

Goodwin and Kanarek had submitted a 1 and 1/2-page letter to Washington Township municipal officials detailing what they saw as a series of code violations, which sent the officials out in force the day before the shooting.

Christianna Cooke-Gibbs, the health officer who was involved with permitting at the farm since the late 1990s, recalled Barisone as a “competent, dignified, elegant man.” But when she came to the property on Aug 6, 2019, she saw someone “very different,” from the person she had known for so long, calling him a “very distraught, very disheveled man.”

She noted work that required permits was unauthorized, and the septic situation at the barn was not designed to handle people living on the site, rather than just working there.

When other officials talked with Goodwin, she stayed away.

“I just got a bad feeling; I don’t know why,” she said.

Fire official Matthew Lopez considered the situation in the house and barn from his perspective as “an imminent” hazard and ordered everyone evicted, with a $5,000/day fine for the property owner if anyone stayed in the buildings. However, he allowed Kanarek and Goodwin to stay after they sent him videos showing the smoke alarms were in working order, even though he did not go out and reinspect the building.

Edward Bilinkas goes over material with fire inspector Matthew Lopez. (Photo © 2022 by Nancy Jaffer)

There was testimony from people in the paramedic, EMT and medical fields about Barisone’s injuries, which included hematomas on both sides of his head, a “deformed” left elbow, bites near his groin area from Kanarek’s dog, a Rottweiler mix, and lacerations, among other things.

In an online posting, Kanarek said she had beaten Barisone on the head with a phone as he struggled with Goodwin in the chaos after the shooting.

Firefighter/paramedic Daniel Vitale called Barisone “confused,” and cited “altered mental status” when he was treating him.

When asked about what had happened, Morris County Supervising Assistant Prosecutor Christopher Schellhorn quoted Vitale reporting that Barisone replied, “Someone drove down my driveway and said she was going to take my kids. That’s all I remember,” adding he said his “heart was hurting, but not physically.”

Barisone does not have children, but his girlfriend at the time, Mary Haskins Gray, had two children.

Although the shooting happened on the day a caseworker from the state Division of Child Protection and Permancy came to the farm to talk with Gray, it has not been determined in the trial who called DCPP. It did come out in testimony last week, however, that Kanarek had searched for the agency’s hotline number on her phone. Barisone drove to the farmhouse where Kanarek and Goodwin lived after the caseworker had made her appearance.

Michael Barisone getting ready to leave court for the day and go back to the Morris County Correctional Facility. (Photo © 2022 by Nancy Jaffer)

Bilinkas seems to be trying to make a case that Barisone was beaten before the shooting took place, but some of his questions were viewed by Judge Stephen Taylor as an effort to “impeach” witnesses; that is, point out discrepancies in their testimony to hurt their credibility. The judge said after the jury had left the courtroom that, “when you impeach a witness, that attacks their credibility, it’s not substantive evidence. It doesn’t mean the shooting happened after Mr. Barisone was beaten and attacked.”

He added, “If you want to argue to this jury that someone beaten with a phone and having a dog bite on his groin is worse than being shot in the chest, have at it. You can make that argument. We’re not here to compare injuries.”

by Nancy Jaffer | Apr 1, 2022

Funeral services will be held next week in Peapack for Joan Scher of Bedminster, known for riding side-saddle with the Essex Foxhounds and her devotion to a variety of equestrian causes.

They included the U.S. Equestrian Team Foundation and the Gladstone Equestrian Association. She also served as a District Commissioner of the Somerset Hills Pony Club. A director of Weber & Scher Manufacturing Co., she was active at St Bridgid’s church, where a funeral mass will be held at 10:30 a.m. April 6.

Mrs. Scher, 86, died March 19. She is survived by her sons Douglas (Ann) and Greg (Lee) Scher, as well as six grandchidlren and two great-granchildren.

Donations in her memory may be made to Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital Somerset.

by Nancy Jaffer | Mar 30, 2022

It was a difficult day at the Michael Barisone attempted murder trial in Morristown, N.J., as his former student, Lauren Kanarek, talked about her wounds, wiping away tears as she recounted the incident that led to her hospitalization for three weeks.

The anguish Barisone feels shows in his face, while he listens to the details of how his life unraveled during the proceedings before Superior Court Judge Stephen Taylor.

Kanarek met Michael at a 2018 clinic and he invited her to come to his farm in Long Valley, N.J. to train so she could reach a higher level of the sport. But things turned toxic in 2019, Barisone was at his breaking point and a downward spiral ended in tragedy when Kanarek was shot two times at point-blank range.

To read my story about what happened in court today, click here.

Here are a few more photos:

Michael Barisone in court. (Photo © 2022 by Nancy Jaffer)

Lauren Kanarek uses a pointer to guide the jury’s eyes toward a portion of a photo in the courtroom as Morris County Supervising Assistant Prosecutor Christopher Schellhorn looks on. (Photo © 2022 by Nancy Jaffer)

The jury saw a photo of the scars left on Lauren Kanarek by two bullets.

Lauren Kanarek relives her shooting in front of the jury. (Photo © 2022 by Nancy Jaffer)

by Nancy Jaffer | Mar 29, 2022

Dressage trainer Michael Barisone was “in an almost catatonic state” in mid-summer of 2019 as he feared for the safety of those around him and his business, viewing threats posted on social media by a boarder/tenant and other harassment with such alarm that he wasn’t eating or sleeping, his former assistant trainer testified today.

Justin Hardin was on the witness stand at Barisone’s attempted murder trial in Morristown, N.J., where he was asked if Barisone was depressed in the days leading up to the Aug. 7 shooting of Lauren Kanarek.

“Extremely,” came Hardin’s reply, noting that for the first time in the 18 years he had worked with Barisone, the 2008 U.S. Olympic dressage team alternate was withdrawn and couldn’t run his Hawthorne Hill stable in Long Valley, N.J., as usual, not even bothering to ride.

Justin Hardin, who worked as assistant trainer at Barisone Dressage. (Photo © by Nancy Jaffer)

When the trial opened yesterday before Judge Stephen Taylor, Barisone’s lawyer, Edward Bilinkas, recounted a saga of harassment by Kanarek and her boyfriend, Rob Goodwin, citing recording of private conversations, the threatening posts and disruption of his client’s home and business. The attorney is pursuing an insanity and self-defense strategy against the charges faced by Barisone, which also include two weapon possession counts.

Kanarek, who began riding with Barisone in 2018, was living in the trainer’s house with her boyfriend, Rob Goodwin, a carpenter doing work on that structure and elsewhere around the property. But their relationship with Barisone and his girlfriend, Mary Haskins Gray, turned sour. Barisone wanted them out, and was moving to evict them.

To get away from the couple in the meantime, Barisone and Gray moved out of the home into a clubhouse adjacent to the indoor ring, and eventually into space at the stable. Finally, a desperate Barisone found himself on a mattress outside the barn when he wasn’t walking the property at night because of his security concerns.

Morris County Supervising Assistant Prosecutor Christopher Schellhorn asked Hardin if Barisone had struggles with anxiety and depression before the situation with Kanarek and Goodwin arose.

Mary Haskins Gray on the witness stand.

While Hardin answered yes, he noted that those conditions were “extremely worse” leading up to the day of the shooting, when two bullets fired at point blank range ripped into Kanarek’s chest, leaving her in critical condition.

Also on the stand today was Gray, quite poised during the early part of her testimony, but looking less composed while the questioning went on about texts exchanged between her and Barisone as things spiraled downward at Hawthorne Hill.

Looking up at her from the defense table was Barisone, with whom she had a romantic relationship beginning in 2015 as the two also collaborated on teaching riders and training horses.

Michael Barisone in court.

Barisone, unshaven and wearing a rumpled gray shirt with a striped tie, watched her intently, occasionally wiping his eyes, as he also had done during other testimony yesterday.

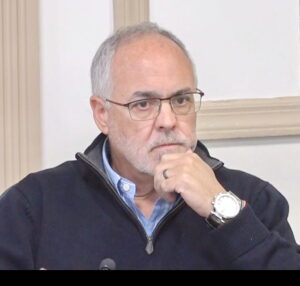

Gray discussed a series of photos of the stable and clubroom with Schellhorn. The championship coolers, ribbons and photos of winning horses on the polished pine-paneled walls spoke of achievement, a sad contrast to the current state of the man who had crafted such success through hard work and horsemanship.

When Schellhorn asked if the atmosphere at the farm had become toxic, Gray replied, “That’s an understatement. We were terrified of what it was building to and what was coming next.”

Focusing on the money it takes to run a top-class stable, Schellhorn drew out Gray on financial issues faced by Barisone, who estimated it cost $40,000 a month to keep his business going. That included monthly payments of $6,000 for the Long Valley property and $3,000 to pay the mortgage on a farm in Loxahatchee, Fla., near Wellington, in addition to all the usual freight for feed, the farrier, veterinary care, maintenance and the other charges horse owners know so well.

Gray also said Barisone told her it was “hard to feel good” after he “got clipped $965,000” in connection with his divorce from Vera Kessels.

Michael Barisone and his ex-wife, Vera Kessels. (Photo © 2009 by Nancy Jaffer

Both Barisone and Gray, as well as Kanarek and Goodwin, in turn complained about the other couple to the U.S. Equestrian Federation and SafeSport.

At the end of July, Barisone texted Gray and told her he wanted information on what Kanarek had done to people in the past.

“I need every single person who has ever been screwed by Lauren, Rob and her dad. Farriers, vets, trainers. I ‘m going to get her a lifetime ban as a competitor,” he vowed.

On August 6, 2019, Gray shipped via UPS 756 pages of information along those lines to USEF counsel Sonja Keating. The shooting took place the next day.

Another discussion about the timeline centered around the SafeSport lifetime ban from the sport of hunter/jumper guru George Morris on the grounds of sexual misconduct involving a minor. The news about Morris, who had been a mentor of Barisone’s, came on August 5.

Two days later, a caseworker from the state Division of Child Protection and Permanency came to the farm to talk to Gray. It is believed that an allegation from Kanarek that Gray’s 11-year-old son had been abused by Barisone was the reason for the visit. There was discussion in court whether the prospect of being banned, after what happened to Morris, was the last straw. Shortly after the caseworker arrived, Barisone drove his pick-up truck to the house, talked briefly with Goodwin, and Kanarek was shot.

Another witness this afternoon was Ruth Cox, the owner of the pink and black Ruger handgun that was used in the shooting.

Ruth Cox and the Ruger.

Cox, who has a doctorate in marriage and family therapy, came to the farm Aug. 1, 2019 to see horses she co-owned with Gray that were in training.

Late one evening, Barisone asked to see the gun she kept with her for safety reasons when she was driving to New Jersey from her North Carolina home. He took it from her and she did not pick it up again until she lifted it today to show it to the jury.

by Nancy Jaffer | Mar 31, 2022

Dressage trainer Michael Barisone’s state of mind in the days before the shooting of Lauren Kanarek was a focal point as his attempted murder trial entered its fourth day in Morristown, N.J.

His former student and tenant, who was shot twice in the chest on Aug. 7, 2019, said under cross-examination by defense attorney Edward Bilinkas that she never threatened Barisone or his girlfriend, Mary Haskins Gray. But when Bilinkas asked about characterizing her social media posts on the subject of Barisone, she conceded, “they could be perceived as threatening.”

Lauren Kanarek on the witness stand.

Was her intention to scare Barisone, Bilinkas questioned.

“Maybe at a point,” replied Kanarek, who also conceded she had written a text saying “Michael is scared,” and indicated to Bilinkas that Barisone was afraid of her father, a retired attorney.

Kanarek and her boyfriend, Robert Goodwin, lived rent-free at a farmhouse on Barisone’s Hawthorne Hill farm in Long Valley, N.J. They paid $2,500 in board per month for each of two horses, while Goodwin did carpenter work on the house and barn to cover the fees for other horses Lauren owned.

Things went sour between the couples during the summer, and the whole farm became embroiled in the toxic atmosphere.

Michael Barisone in happier days at his Hawthorne Hill Farm. (Photo © 2009 by Nancy Jaffer)

Goodwin said Barisone told the staff not to communicate with him and Kanarek. That boiled over when an employee didn’t respond to Kanarek’s concern about a dryer in the stable that wouldn’t turn off, which she saw as a fire hazard.

Kanarek and Goodwin sent a 1 and 1/2-page letter citing “a dangerous and illegal situation” to the Washington Township housing inspector (Long Valley is part of Washington Township) detailing what they saw as code violations.

The result? Township officials descended on the farm Aug. 6 and put up notices telling everyone to vacate the premises. There was a $5,000/day fine if everyone didn’t leave.

Robert Goodwin.

Barisone, sitting at the defense table, had his head in his hands when that topic came up. Bilinkas is pursuing an insanity/self-defense strategy in his defense of the 2008 U.S. Olympic dressage team alternate.

In his opening remarks on Monday, Bilinkas contended that Kanarek, her father and Goodwin devised a plan to destroy Barisone and drive him crazy.

The shooting took place after a caseworker from the state Division of Child Protection and Permanency visited Gray, who had two children. Why did the caseworker come? What allegations were made?

“Was part of your plan to destroy Michael Barisone to contact…DCPP?” asked Bilinkas

Kanarek said no, and added she had never contacted the agency.

But her phone yielded recorded searches for that agency’s number on two dates in July. On July 31, she “did not recall” searching for the agency’s anonymous hotline, adding “but it’s possible.” Then she said she did remember. Lack of recollection came up often in her testimony, until she was shown documentation.

At the same time, she mentioned that Barisone’s assistant trainer, Justin Hardin, earlier that year had “stolen” her phone at a restaurant. Citing his technological expertise, she said he had broken into her phone and it was possible he “may have been able to do things to my phone that I did not.”

On Aug. 7, Barisone asked the caseworker and Gray, who were meeting in his office, to leave. He had kept a pink and black 9 mm gun, the weapon used in the shooting, in the office safe. Moments later, he drove to the farmhouse where Kanarek was living and the incident unfolded.

Michael Barisone in the courtroom.

Goodwin, 42, took the stand later in the day. Like Kanarek, who had a history with heroin, Goodwin admitted to using drugs “anything I could do to get out of my anxiety” under direct examination by Morris County Supervising Assistant Prosecutor Christopher Schellhorn.

When Bilinkas asked Goodwin whether he had used crack, the judge did not permit him to answer the question. Kanarek said earlier in the trial that she has been sober for several years but Goodwin admitted to some relapses while living in Long Valley, though he said he never took drugs while at the farm.

Goodwin said as August 2019 began, Barisone was “making life difficult at the farm for us to want to stay.” Barisone was trying to evict the couple.

Prior to that week, Goodwin said he had hoped “to salvage the relationship. Ultimately, we would (have) kind of liked to work something out.”