When you mention the name of Major Gen. Jonathan “Jack” Burton anywhere in the equestrian world, it instantly sparks admiration.

Now, however, it will bring expressions of sorrow. Word came today that this great horseman died on May 29 in Tucson, Ariz., at age 99.

Jack Burton played a big role in making equestrian sport what it is today in the U.S. (Photo©2018 by Nancy Jaffer)

The personification of dedication and fairness, he was an Olympian who made a seamless transition from the U.S. cavalry to decorated soldier and modern military commander, serving in three wars.

“The ability to lead other men in combat is a rare skill, and he found a home in the Army,” noted Jim Wofford, an Olympic eventing medalist who was a lifelong friend of Gen. Burton.

Jack went on to become a prominent civilian figure on the equestrian scene as well, serving as a judge, steward, committee member and inspiration, remaining an important part of the sport until just a few years before his passing. He served as a horse show official for the last time when he was 92.

He always made it his business to stay fit enough to do his job, whatever it was, and rode with the Loudon, Va., hunt into his 80s.

“He never takes the elevator, even if his room is on the 10th floor,” Sally Ike, the USEF’s director of licensed officials, observed a few years ago. She would always salute Gen. Jack when she saw him, and invariably received a snappy salute in return.

A native of Illinois, Jack was a member of the ROTC at Michigan State College when he graduated in 1942 in the midst of World War II. Four days later, he found himself taking an intensive six-week cavalry course at Fort Riley, Kansas, before being shipped to El Paso, Texas. There, as part of the First Cavalry Division, he patrolled the Mexican border, “looking for spies, saboteurs or whatnot,” he recalled a few years ago when I interviewed him for a story.

He got a good education in riding and horsemanship during college, because in those days, ROTC at land grant schools had horse cavalry or horse artillery, with a detachment of soldiers taking care of horses and a few officers to teach classes.

“The military system was based on the European system,” he explained to me once. The ROTC guidebook was “The Cavalry Manual of Horsemanship and Horsemastership,” vintage 1935. The instruction including shoeing, conditioning and stable management, as well as riding.

Jack Burton in his army days

But his time on horseback once he was serving with the Army turned out be short-lived.

The Australians were light on infantry, since they had shipped four divisions to fight with the British in the Far East, while the Japanese were on their doorstep in New Guinea, bombing Darwin and Brisbane.

So Jack’s outfit, was sent over, without horses, to “clean up New Guinea.”

While he was still in Australia, Burton saw an attractive blonde dancing during a gathering at a hotel.

“I cut in on her, got her phone number and it went on from there,” he remembered.

“When we took the Admiralty Islands, we spent six months building a naval base, and they let us go down to Australia on leave. I called her up and said, ‘Let’s get married.'” He and Joan were married in 194 and had two children, Jonathan Jr. and Judy Lewis. Joan pre-deceased him.

Jack didn’t get back to horses until after the war, when the show circuit started up again following a four-year hiatus.

Although the army had been mechanized, he was assigned to the cavalry school at Fort Riley, where he was the instructor for the last two years that horsemanship classes were held for officers.

Although it was clear that the cavalry was nearing the end of its days, “They finally decided they wanted to send a team to the 1948 Olympic Games in London, since the Army had sent teams to all the previous Olympics,” Jack recollected.

Jack Burton on Air Mail in 1948. USET Foundation archive photo.

He was in the elite group of officers who were getting ready for the Olympics, which had not been held since 1936.

“All we did was train,” he said. “We trained jumpers, three-day horses and what we had in dressage.”

While preparing for the Olympics, the Army team competed in jumping at the biggest shows, including the National at Madison Square Garden, as well as Dublin and Geneva.

“I was a junior officer, so I would travel with the horses. We’d go in baggage cars equipped to haul horses. When we shipped horses to Europe, we went by boat. It took about 11 days. Soldiers would clean the stalls, but I helped,” he remembered.

In 1947, the same year he was U.S. Three-Day Eventing Champion, Jack won the National Horse Show’s international individual show jumping trophy with Air Mail, beating the legendary Mexican General Humberto Mariles, whose country’s teams dominated the competition at the National for a decade.

Although Jack was selected for the 1948 Olympic jumping and eventing teams, his horse went lame and he found himself in the position of helping his teammates as reserve rider. It was the last gasp for the cavalry in the Olympics.

After the Army gave up its team in 1950, the fledgling U.S. Equestrian Team was formed. Jimmy Wofford’s father, 1932 Olympian Col. John “Gyp” Wofford, the USET’s first president, asked Jack, who was in Europe with the Army horses, to bring back any he thought could be candidates for the 1952 Olympics.

“I returned by boat with 12 horses that could be used on the team, one of which was Democrat. He could jump, he could three-day and he could dressage. He was a thoroughbred bred by Gordon Russell in the army remount system,” Jack had recounted.

“When we had 14 regiments of cavalry, we had to buy thousands of horses. The highest price buyers could pay for a horse was $165.”

Jack chose well. The fledgling USET won the bronze in eventing and show jumping, with Democrat playing a role in the latter success, then going on to major victories at the National Horse Show and elsewhere.

While Jack had hoped to ride on the 1952 Olympic team in Helsinki after missing his chance four years earlier in London, the Army had other plans for him. After serving in Korea, however, he finally made the eventing squad in the 1956 Olympics.

He fell off Huntingfield when the horse stumbled coming off an 11-foot drop on cross-country.

“In that day, we had a phase E after cross-country,” said Jack, who was picked up by his horse’s owner and thrown back into the saddle so he could complete the test.

“The horse galloped phase E, 1,000 meters, but when I arrived at the finish line, the Swedes there saw I was noncomprehensible and put me in the ambulance.”

After doctors determined Jack had a concussion, they said he shouldn’t ride in the jumping phase the next day. He followed their advice.

“There was no point, because one of the other U.S. riders got eliminated in jumping and the other was eliminated in cross-country. But I probably should have,” he said wistfully, “so we at least could have had a horse finish.”

That wasn’t his last experience with the Olympics, as his involvement with horse sports took another turn when he became an official. He judged eventing at the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics, as well as the 1966 World Championships in Burghley, England, and the 1982 World Championships in Luhmuhlen, Germany. At the Atlanta Olympics in 1996, he was on the appeals committee.

After two tours of duty in Vietnam, Jack retired from the military in 1975 as commander of the Third Armored Division and went on to be executive vice president of the USET.

Following World War II, there was nothing in the way of civilian eventing. The sport was known as “the military,” appropriate since it had started as a test of cavalry officers’ mounts.

“The Army once a year had an Olympic-level three-day event. It was the graduation of the advanced (officers) course. That was the only eventing in the U.S.,” Jack remembered a few years ago.

A correspondent for the Nashville Tennessean newspaper contacted him when he was stationed at Ft. Knox, Kentucky, asking him to come to Tennessee and help put on a civilian event in 1953.

“We went down to Percy Warner Park, where there was a steeplechase course. We added some tires and barrels and made a cross-country course. We didn’t have a rulebook, so I copied the FEI rulebook,” Jack said.

What would be a training/preliminary-level event today, attracted about a dozen riders, including some from Canada, and the sport grew from there.

“Denny Emerson (a former president of the U.S. Eventing Association) referred to Jack as the Johnny Appleseed of the eventing world,” recalled Jimmy Wofford.

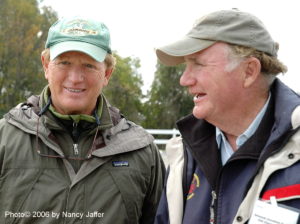

Jack Burton with Jimmy Wofford. (Photo©2006 by Nancy Jaffer)

“Wherever Burton would be stationed, suddenly an event would spring up. He got Pony Clubs involved in it; he got local combined training associations started. The interesting thing is that after he left, they still kept going, so he must have had some knack of developing things that could stand on their own two feet and didn’t depend on Gen. Burton being there.”

Jack adapted well to change, knowing from his experience in the military when to argue against it and when to fall in line and accommodate it. He served as president of the U.S. Combined Training Association (now the U.S. Eventing Association) and wrote the first U.S. rulebook for eventing.

He will be interred at Arlington National Cemetery last this year, and his memory will be honored in December at the USEA’s annual meeting in Boston. Jack was among the last of a great generation of horsemen, and we salute him.